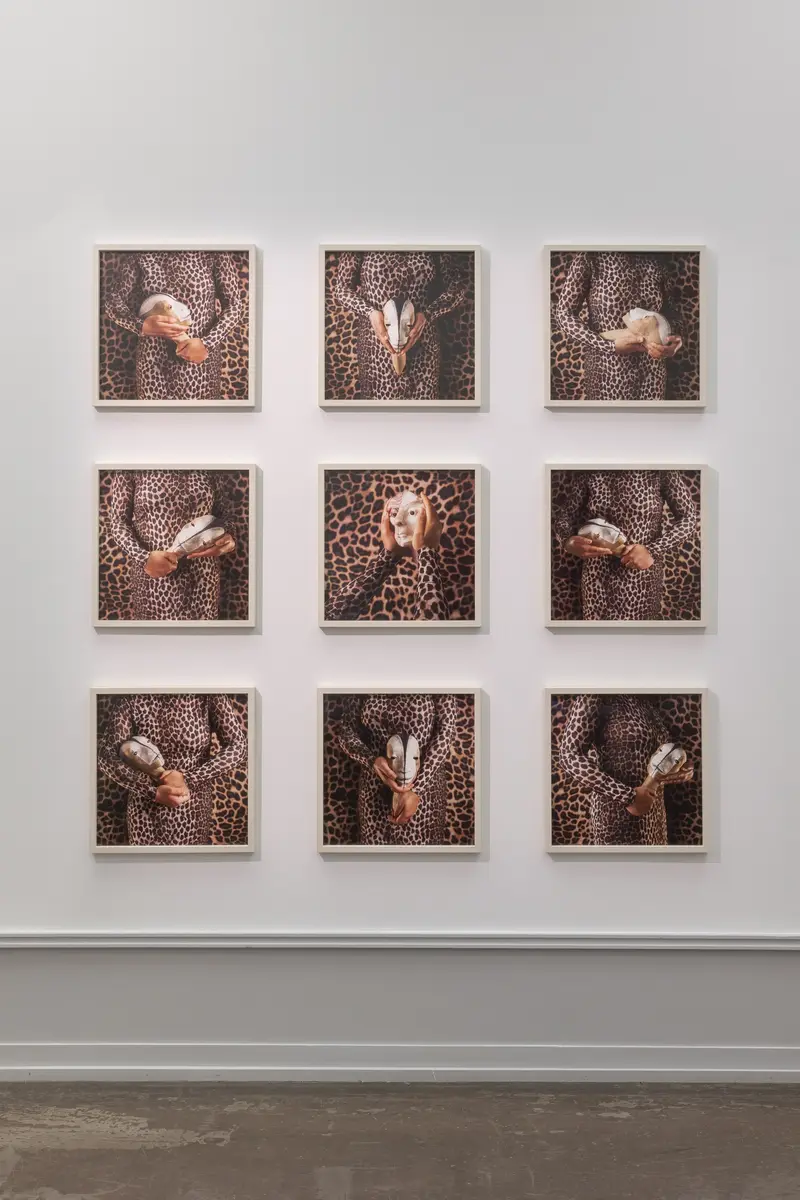

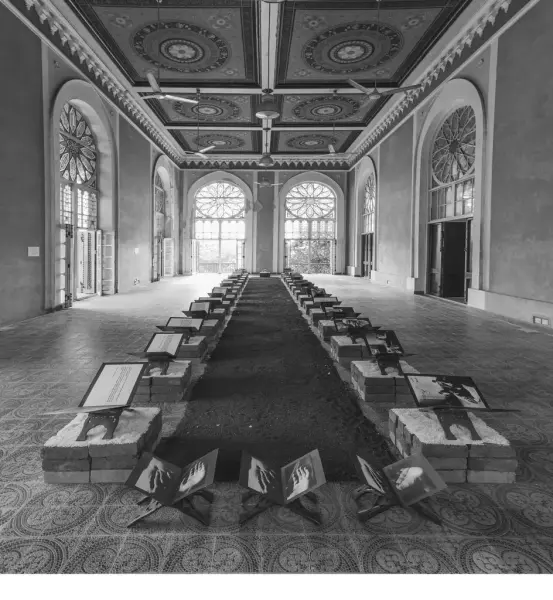

Passing Motherhood is an international group exhibition that explores the many dimensions of motherhood.

How is motherhood shaped by politics, history and migration? How do war, displacement and inheritance affect the relationship between mothers, children and society?

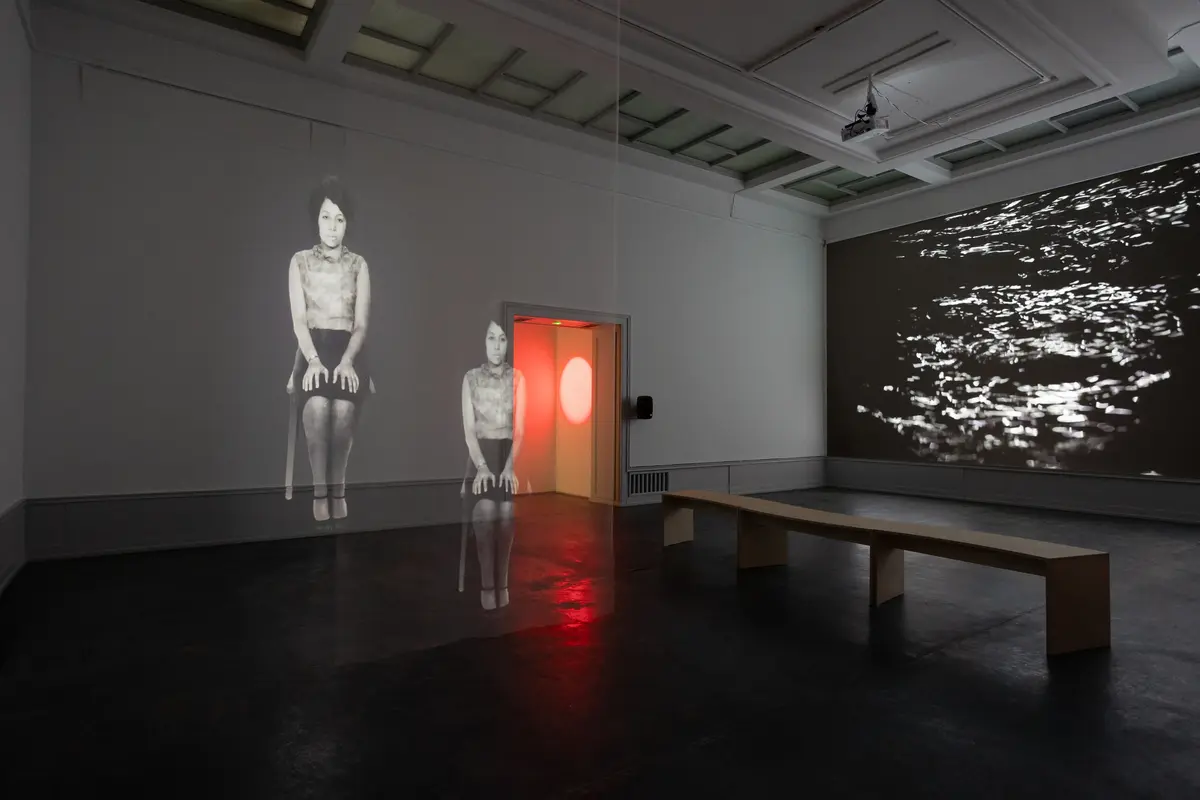

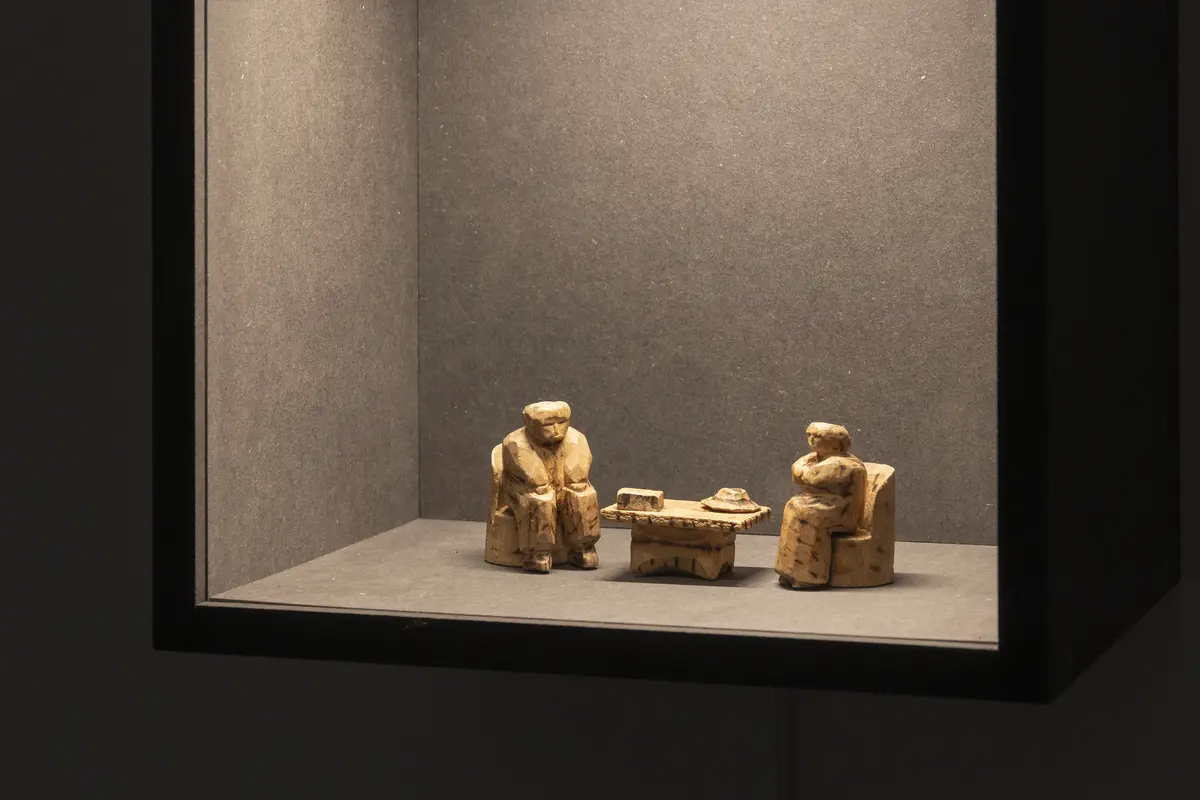

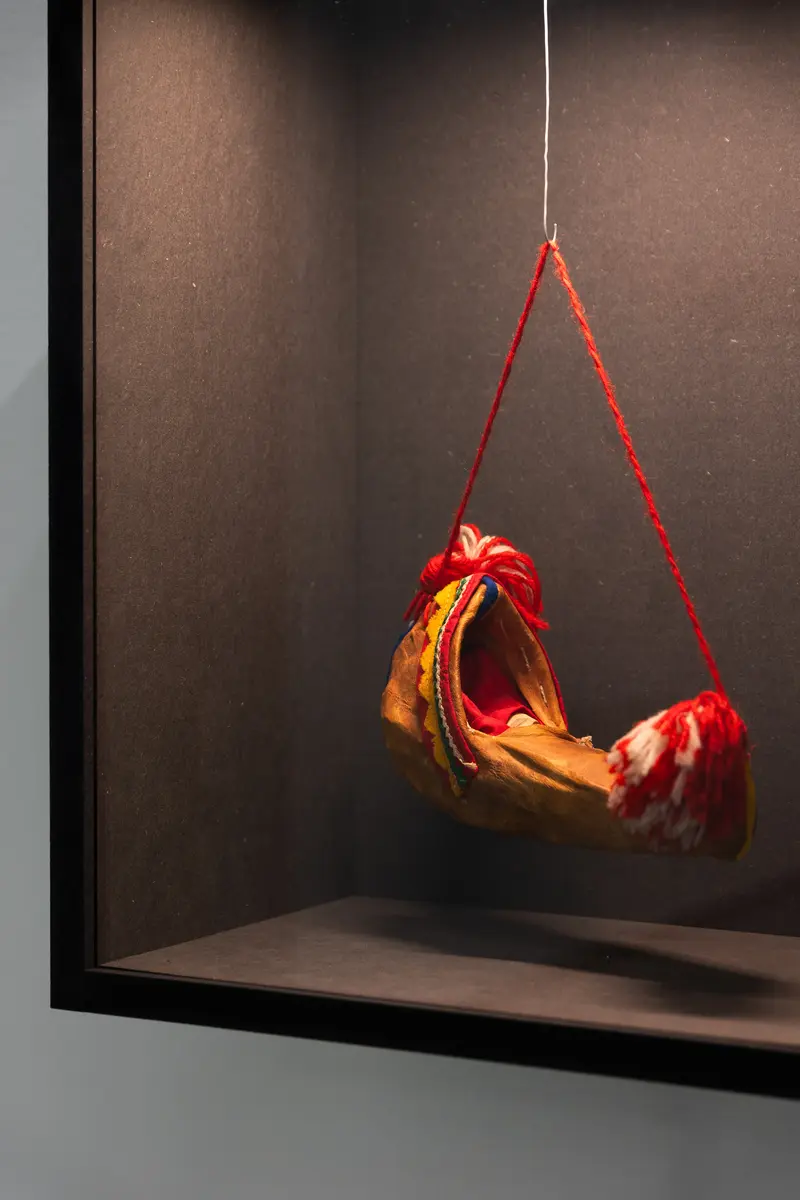

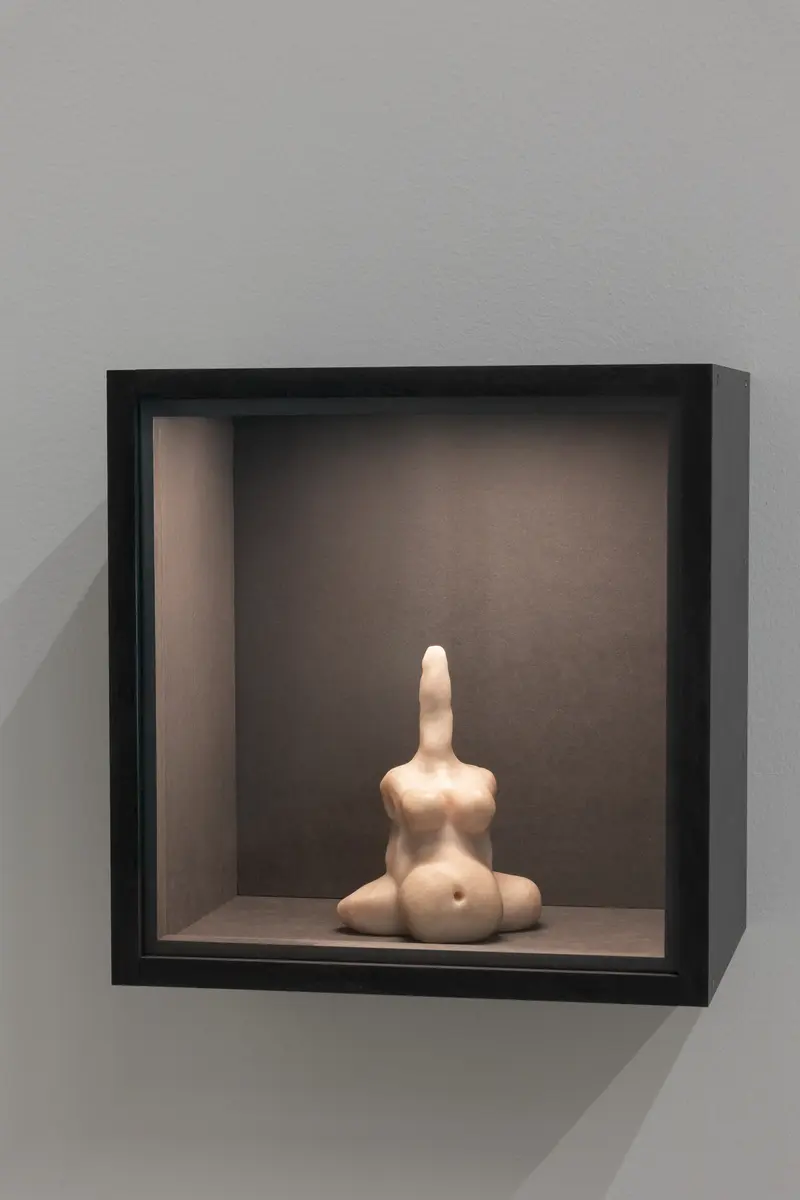

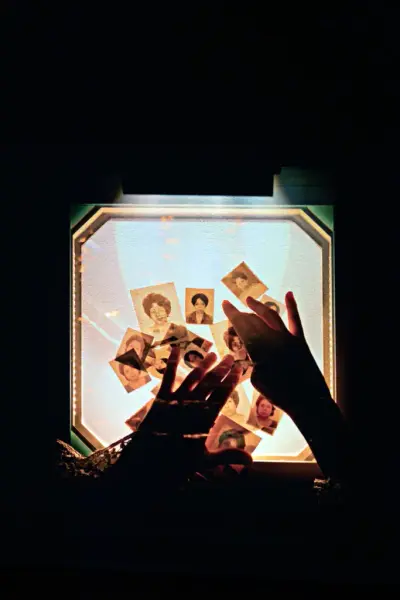

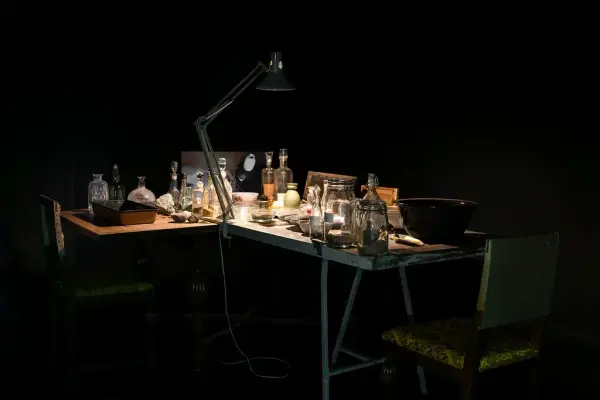

The exhibition is kaleidoscope of perspectives: from personal memory and embodied practice to colonial histories and institutional critique, and from the technological mediation of care to centuries-old ritual objects that have crossed borders and epochs.

These works remind us that “motherhood” is an ever-shifting, multivalent state. It cannot be limited to biology or sentimentality, just as it cannot be pinned down with a single geographical pin. Instead, they demonstrate how motherhood is transmitted — through bodies through bodies, cultural structures, words, silence, traumas, images, crafts and gestures of resilience.

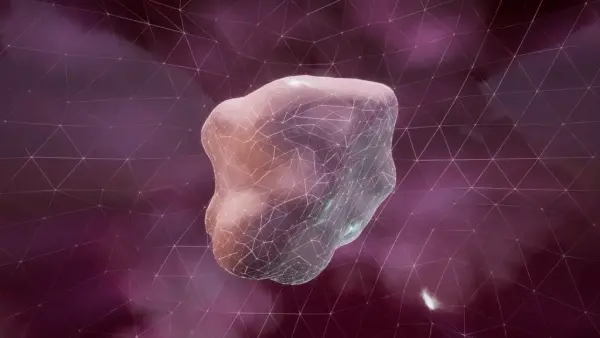

A tapestry woven in defiance of war, a glimmering sphere of compressed earth, a digitally programmed “cyber child”, or the sound of someone else’s mother tongue; all offer a distinct perspective on care, birth, inheritance and the sociopolitical contexts that shape how we carry one another across time.

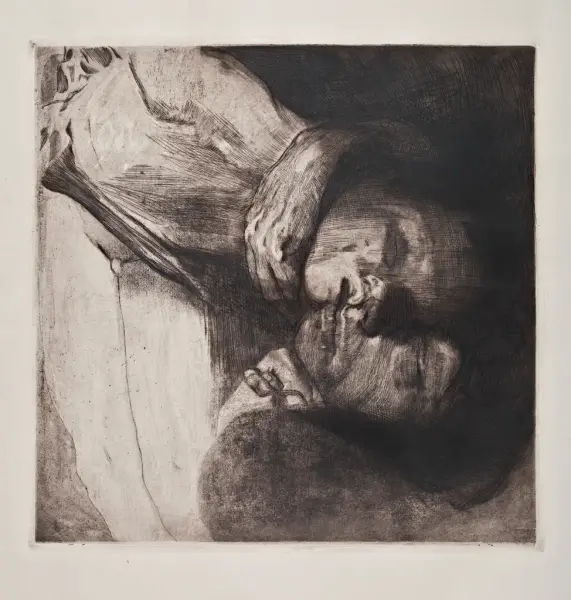

Participants: Aine Motta, Athena Farrokhzad, Basma Al-Sharif, Elise Storsveen, Gitte Dæhlin, Maritea Dæhlin, Lisbeth Dæhlin, Guttormsgaards arkiv, Hannah Ryggen, Käthe Kollwitz, Louise Bourgeois, Marin Shamov, Nils Aas, Sheba Chhachhi and Sonja Jabbar, Thora Dolven Balke, Veslemøy Lilleengen and unknown authors.

Curators: Yaniya Mikhalina and Marianne Zamecznik

Project manager: Lisa Størseth Pettersen

The exhibition is Trondheim Art Museum's contribution to the Hannah Ryggen Triennale 2025; MATER.

At first glance, Passing Motherhood might seem to revolve around a single, contained theme: the experience of mothering. Yet from the very beginning, the exhibition demonstrates how motherhood, in all its sensible and political dimensions, stretches far beyond the individual plane — reaching into questions of land and belonging, war and displacement, memory and inheritance, and the institutional frameworks surrounding it. The artworks, archival materials, testimonies and historical objects assembled in the context of the exhibition underscore the vast network in which “motherhood” is ceaselessly created, contested, and transferred — across bodies, geographies, and generations. In this polyphonic landscape, we recognize the threads — or routes — with which the exhibition can be experienced. The act of mapping is an invitation to the creation of a route of one’s own, as it is the viewer’s experience that gives birth to the new relationships between the works.