Podcast

Listen to Basma al-Sharif speak about her artistic practice and the new film Morgenkreis, which will be featured in the exhibition Passing Motherhood at Trondheim Kunstmuseum starting June 20, 2025.

Language: English

- 1/1

Duration: 14 min 51 sec

Basma al-Sharif

Morgenkreis (Morning Circle), 2025

a film, workshop and research project

In “Colonial Object Relationships,” David L. Eng connects the European Enlightenment project — and its role in shaping European liberal subjectivity — to the “war in the nursery” described by Freud in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.” In this text, Freud conceptualizes the emergence of the death drive in the infantile psyche by observing his 18-month-old grandson. To cope with his mother’s comings and goings, Freud’s grandson Ernst famously plays fort-da, throwing and returning the wooden reel by its string. This repetitive action symbolizes the introjection of the reality principle.

A year later, Ernst takes the same toy and throws it on the ground, claiming to send it “to the front,” where his father was stationed at the time. Freud links this event to the segregation of love and hate between “beloved mother and rivaled father.” David L. Eng goes beyond conventional Oedipal interpretations, instead looking at the difference in objects produced by the European colonial condition:

…Attention to colonial object relations reveals the ways in which affect is unevenly distributed in the history of liberal empire and reason. It exposes how love and hate are affectively policed to create a field of good and bad objects and liberal and indigenous subjects, regulated by a colonial morality that is not the cause but rather the effect of processes of repair.

In his reading, reparation is the fantasy of a white liberal subject. The question is, when and where do we see it emerge in daily life?

Basma al-Sharif’s new project, Morning Circle, necessarily traverses different forms, simultaneously existing as a research project, a workshop, and a 16-mm film. It opens a space for critical reflection on Western cultural hegemony through the seemingly benign environment of a kindergarten. As an institution invented in Germany in the 18th century, the kindergarten has played a crucial yet shadowed role in maintaining the European liberal project, its colonial morality, and the fantasy of assimilating the Other, intensified by the ways in which the state shapes a process of primary separation.

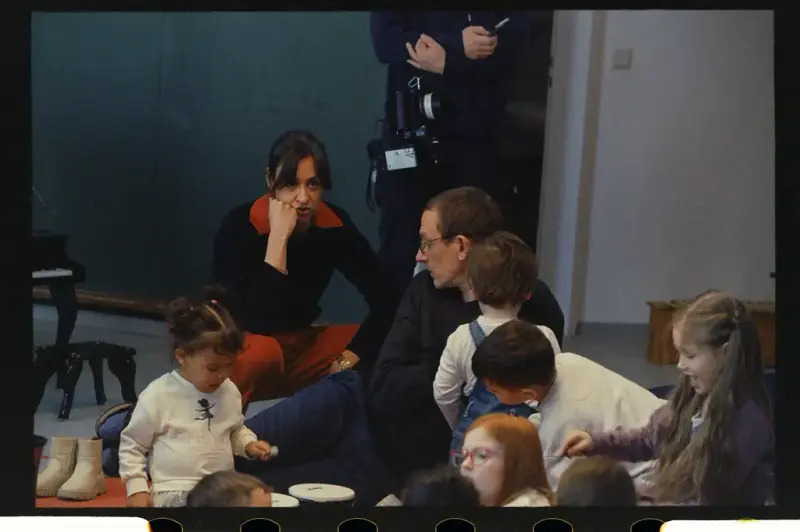

As a Palestinian artist living and working in Germany, al-Sharif confronts a complex situation: a state that negates the reality of the genocide in Gaza and any expressions of solidarity against it at the governmental level, while maintaining a monopoly over childhood education (homeschooling in Germany is illegal). Through her work, Basma performs a necessary ethical act. She reveals the connections between these two seemingly unrelated foundations upon which the emergence of the good white liberal subject and the bad colonial object rests, as well as the morbid hierarchies these foundations perpetuate. In the film, the artist stages a revolt by a group of preschool children against the typical morning ritual of gathering in a circle to sing a song together to start the day.

In keeping with the unpredictable schedule of birth, the final film will premiere in the middle of the exhibition period. Meanwhile, a collection of images documenting the rehearsals for the film, as well as the script, will be presented as an installation.

- Yaniya Mikhalina

Photo: Galerie Imane Farès

Basma al-Sharif (she/her, b.1983, Palestinian) is an artist/filmmaker. Her work explores cyclical political histories and conflicts through films and installations that move backward and forward in history, between place and non-place, in order to confront the legacy of colonialism through satirical, immersive and lyrical works. Al-Sharif received an MFA from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 2007. Recent exhibitions include: Après la fin. Cartes pour un autre avenir, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2025; The Place Where I was Condemned to Live, De Appel, Amsterdam, 2024; Basma al-Sharif: Capital for the Ruttenberg Contemporary Photography Series, Art Institute of Chicago, 2022; and the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2022. She was a fellow in the Berlin Artistic Research Grant Programme for 2022–2023 and was nominated for the Prix Aware for 2024. Al-Sharif is represented by Imane Farès Galerie in Paris and lives and works in Berlin.

Production credits

Basma al-Sharif, Morgenkreis (Morning Circle), a film, workshop and research project, 2025

Concept, Script, Direction: Basma al-Sharif

Producer: Eyal Vexler

Assistant Director: Rozeen Bisharat

Director of Photography: Simon Veroneg

Gaffer: Golo Jahn

Sound Designer: Federico Chiari

Wardrobe and Props: Antonia Eckardt

Production Assistant: Ramez Melhem

B&W Photography: Mariam Mekiwi

Music: Maurice Louca: Benhayyi Al-Baghbaghan (Salute the Parrot)

Lead Actors: Mohmmad Ali, Panos Aprahamian

Supporting Actors: Fadi AbdelShafi, Jasmina Metwaly, Philip Widman

Background Actors: Soraya, Leyla Rosa, Emilia E., Aurelia, Ana, Mia, Emilia, Sami, Henrix, Damian, Emilio, Alexey, Sam, Milan

Commissioned by the Vega Foundation, with support from de Appel, the Gwaetler Stiftung, the Sharjah Film Production Program, and Trondheim Kunstmuseum