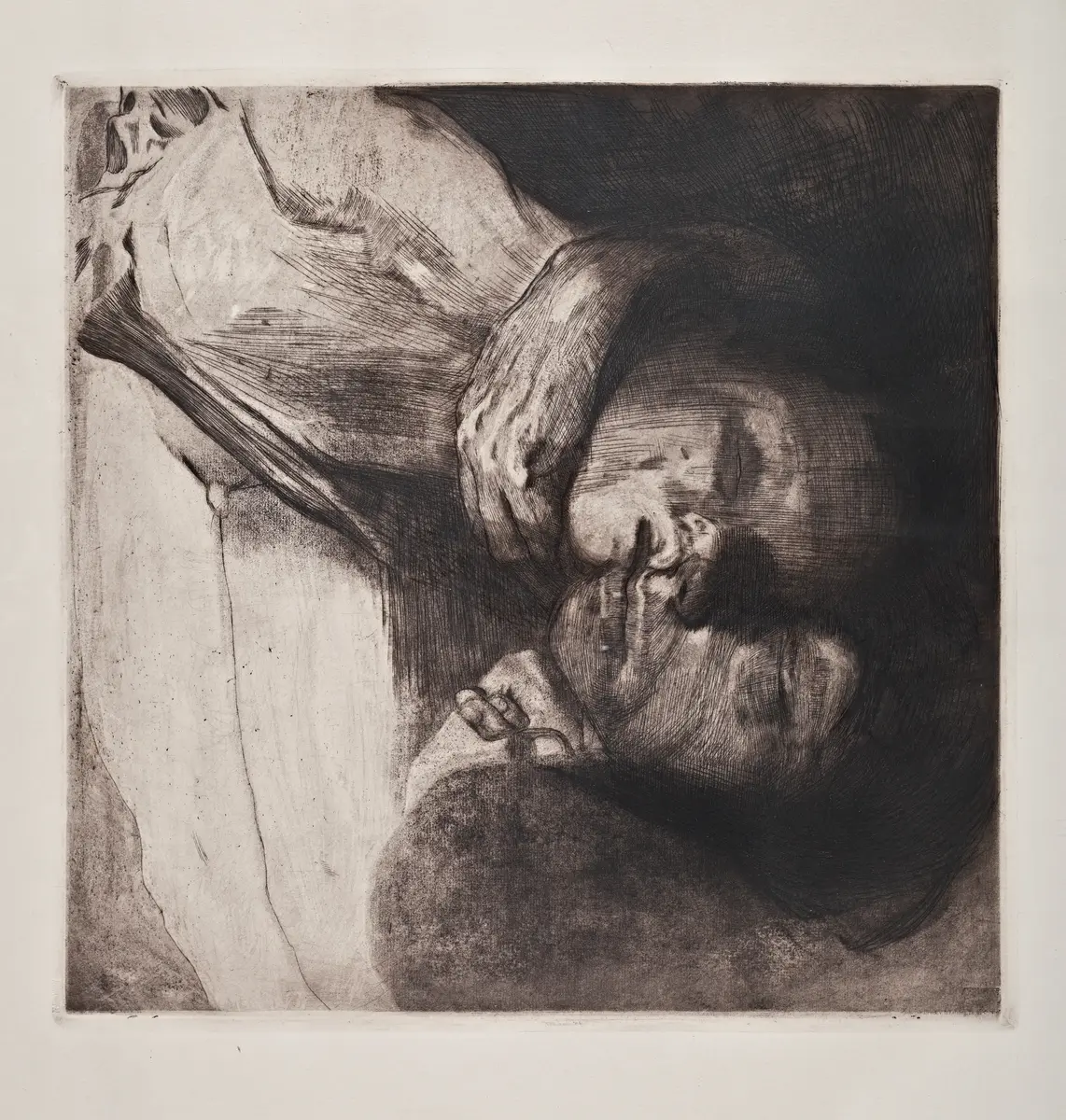

Käthe Kollwitz

Tod, Frau und Kind (Death, Woman and Child), 1910

etching

58.5 x 59.5 cm

From the collection of the Guttormsgaards archive

Along with production of wars, each epoch has constructed distinct strategies for representing human suffering. For Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) and her time — the late 19th and early 20th century — art undoubtedly considered its goal the humanization of those subjects most affected by warfare: working-class mothers. “Working class” almost sounds too elaborate, as the depth of their poverty — and grief — is inconceivable. This term reflects an archaic class consciousness rather than the actual one. It has yet to emerge from the depths of sorrow and anger of those who have nothing left to lose. Faces melt into each other; bodies exist the same state of decay as their environment — all black and white. Figures exist in an eternal process of development, slowly emerging from the emptiness of the sheet, like a Polaroid in its first minute of exposure

Kollwitz’s later etching Tod, Frau und Kind (Death, Woman and Child) is widely considered to be a reflection of her fear as a mother in the face of the possible loss of her son to serious illness, as well as her own mother's grief at losing three children in infancy. The work resides in collections worldwide, including Guttormgaard’s archive in Norway. Kollwitz’s choice of the printmaking medium reflects the artist's commitment to socialist principles of accessibility and collective ownership in the arts. She further elevates poverty via the labor-intensive technique of printmaking, while simultaneously perpetuating the quiet violence of representing the suffering of the Other through the repetitive image-making process. In this, there is an echo of the hierarchical display of pain which is not one’s own. While the distress becomes sublime in the final art work, it is still very much part of the discourse of the Other. Viewing this work from our media-saturated present in which the fetishistic desire to “look at someone else’s suffering” is fully indulged, the concept of humanized poverty may feel obsolete. Yet, it remains as relevant as ever.

- Yaniya Mikhalina

Käthe Kollwitz,1914/1917 Foto: Hänse Herrmann/Deutsche Fotothek

Käthe Kollwitz (she/her, b.1867, Königsberg – 1945, Moritzburg) was a German graphic artist and sculptor. Her work depicted the human condition, focusing on war, poverty, and social injustice through expressive drawings, etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts. She studied at the Women's Art School in Berlin and the School of Art in Munich. She became the first woman elected to the board at the Berlin Secession in 1906 and had multiple shows at Emil Richter's gallery in Dresden. Kollwitz also exhibited internationally at the Women's Art Club of New York (1917) and had exhibitions in Moscow and Switzerland during the 1920s and early 1930s. However, after the Nazis came to power in 1933, her work was removed from public view and she was forced to resign from the Prussian Academy of Arts. Kollwitz lived and worked in Berlin until her death.

Production credits

Käthe Kollwitz, Tod, Frau und Kind (Death, Woman and Child), etching, 1910

From the collection of the Guttormsgaards archive

Thank you: Ellef Prestsæter