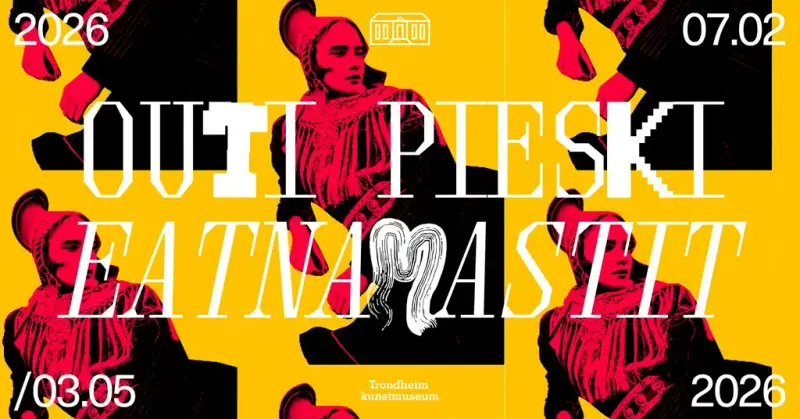

Outi Pieski – Eatnamastit

Trondheim Kunstmuseum presents the most comprehensive exhibition in Norway to date of the Sámi-Finnish artist Outi Pieski.

Based in Ohcejohka (Utsjoki) on the Finnish side of Sápmi—the ancestral land of the Sámi people, inhabited for thousands of years long before today’s national borders—Pieski’s work engages with Sámi history, philosophy, and culture, and how these continue to shape Sámi life today.

The exhibition brings together around fifty works, offering a multifaceted view of her artistic practice. Through painting, photography, textiles, video, printmaking, and installation, Pieski explores the relationship between humans and nature. For her, the act of creating art is a deeply personal and strengthens the connection to landscape and nature, both within and around us. From a Sámi perspective, humans do not exist above nature but in a position of mutual dependence: we coexist with all living beings in reciprocal respect. Nature is understood as an interconnected system, where all beings—visible and invisible—are related and reliant upon one another.

The exhibition’s title, Eatnamastit, derives from a new work created specifically for this presentation and commissioned by Malmö Konstmuseum. The term may be understood as the act of grounding and anchoring oneself in nature. As a recurring theme throughout the exhibition, the landscapes of her home region appear both as subject matter and as a source of inspiration and identity. In Pieski’s art, the landscape embodies the lived experiences and memories of her own and earlier generations.

In a Norwegian context, Pieski’s significance is further highlighted by her commission for one of the most important public art projects in Oslo’s new Government Quarter. Her monumental artwork AAhkA draws on Sámi beliefs and philosophy, invoking Mother Earth as a legal entity. The title also refers to sacred mountains in Sápmi that bear this name. In Southern Sámi, Aahka, and in Northern Sámi, Áhkku, the word translates as “grandmother,” “elder woman,” and “protector of the earth.”

Educated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki (2000), Pieski has established herself as one of the leading artists from Sápmi. She has presented solo exhibitions at Tate St Ives (2024), Sámi Museum Siida (2023), Bonniers Konsthall (2022), and EMMA in Espoo (2018). Her work has also been featured in group exhibitions at Tate Modern (2025) and MARKK, Hamburg (2023–24), as well as in major international biennials including the Venice Biennale (2019), Gwangju Biennale

(2021), Biennale of Sydney (2022), and GIBCA – Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art (2023).

Eatnamastit is produced in collaboration with Malmö Konstmuseum in Sweden.

The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Malmö Art Museum.

Curated by arbeid med Malmö konstmuseum.

Curators: Anna Johansson, Marcus Pompeius and Marianne Zamecznik

Themes in the exhibition

Relationship with the Land

Outi Pieski’s art has a strong connection to the land. In the traditional Sámi worldview, humans are not above nature but instead share living spaces with plants, animals, and spirits in continuous communication. An important Sámi practice involves asking for permission. Permission to cut down a tree, pick berries, or shooting an animal. Through contact with all living things, a person is thus able to feel the answer in their body. Consequently, all that is taken from nature is considered a gift. Living in communication with all living things permeates everyday life, which is especially noticeable in the philosophy surrounding the craft of duodji or the handling of animals. In a Sámi context, the word ‘spirituality’ is therefore seen as inadequate because it presupposes that the belief system can be separated from everyday life.

For the early Christian colonisers, the Sámi view of nature and religion was intriguing, yet simultaneously inferior or sinful. Today, when the majority society has become more accepting of different world views, Sámi traditions has instead in some cases, been idealised. As a result of Western hunger for spirituality the Sámi as a people has been exoticised. Still, the Sámi traditional lifestyle as reindeer herders and hunter- gatherers has shaped their knowledge of natural resources, which involves not only understanding the life cycles of animals and plants, but also how weather, wind, and the seasons affect the landscape and the habitats they depend on. This understanding of the world has not only survived in the Sámi culture, but continues to be a living part of Sámi identity and worldview today.

Foremother’s Hat of Pride

Ládjogahpir is a headdress worn by women in the northern parts of Sápmi before the use was banned in the late 19th century. The horn, which is called a fierra, is made of birch or pine. In a research project conducted with archaeologist Eeva-Kristiina Nylander, Outi Pieski has sought to revive the headdress in the culture today as a symbol of empowerment for contemporary Sámi women. By organising workshops with Sámi women learning to recreate the ládjogahpir, Pieski and Nylander have been able to create a space for healing and for sharing ideas, values, and dreams. They describe this as ‘craftivism’, activism where craft is used as a medium to empower participants.

Art institutions have historically upheld dominant power structures that discriminate against and devalue different cultural heritages. In her practice, Outi Pieski has questioned why Sámi visual and cultural traditions are displayed in ethnographic museums, while Western art is shown in art galleries. The ládjogahpir can be seen as a symbol of a new decolonial feminism where it plays an active role in the work of re-remembering, decolonising, and healing. By again wearing the ládjogahpir, women are changing the spaces they enter. The project has spread

across northern Sápmi and into the private spaces of women’s homes and the spaces where they wear their headdresses—at meetings, protests, weddings, funerals, parties, and public speeches.

Duodji

A prominent role in Outi Pieski’s art is held by duodji, a complex concept that can be translated as both art and craft. Duodji encompasses Sámi philosophy, values, and spirituality with practical and traditional knowledge, and the whole sphere of artifact making, from clothing and utensils such as knives, drinking vessels and storage containers, to jewellery, ornaments, and beautiful design patterns. The concept combines practical skills with a strong relationship to both the materials and the objects being made. The materials are active co-creators. A relationship between the artist/duojár and the materials leads to the person for whom duodji is made; those who use and live with the objects. The colonisation of Sámi culture and the land area of Sápmi resulted in duodji being overrun with industrial products. Still, the tradition has persisted and is today a strong identity creator and culture carrier.

The Western tradition of ideas mostly sees creativity as belonging to an individual. Duodji instead emphasises collective creation, where each generation adds something to the work of previous generations. Historically, duodji has been created with materials provided by nature, such as skins, birch bark, reindeer antlers and tendons. Today, modern industrial materials and techniques are also included in duodji. Its meaning has also been reconsidered and redefined many times over.

When the Sámi people were prohibited from practicing their spirituality, craft became a form of resistance, spiritual symbols were hidden within the making. For Pieski, working with duodji is a method for healing intergenerational trauma and for reaffirming the bond with the landscape and all living things. She uses the term “radical softness” to describe how duodji embraces vulnerability, honesty, sensitivity, and community.